Australia. It compares well to Canada by being a large country, with a low population density and extreme temperatures. It is also among the peer group of countries that phone and Internet service prices in Canada are often compared against. We argue that a country’s performance in this sector ought to be judged in its entirety and not just on price.

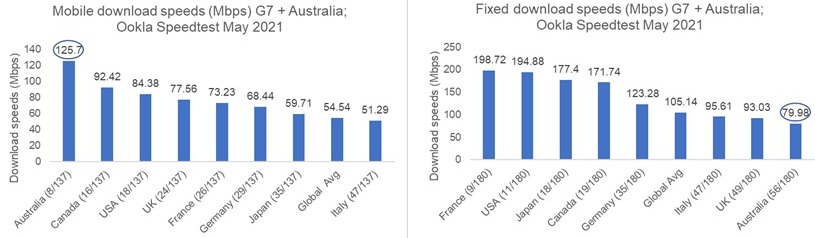

There is something contradictory about the performance of Australia’s broadband market. It has the highest download speeds for mobile broadband and the lowest for fixed broadband as per the latest Ookla Speedtest report¹.

How did we get here?

The Australian wireless market consolidated from 4 national operators to 3 in 2010, when Vodafone Australia merged with Hutchison Telecommunications Australia to form VHA. The market is now comprised of Telstra with 49.2% share, Optus at 33% and Vodafone at 17.5%, making it a more concentrated market than Canada².

Australian wireless operators are all national, with no regional players, and it has MVNOs. The market share for MVNOs (Mobile Virtual Network Operator or Resellers) has been falling and they make up around 10% of the market. This is equivalent to the market share of Canada’s regional wireless operators (Shaw, Videotron, and Eastlink). The difference of course, is that the regional operators in Canada have invested capital to build out infrastructure, whereas the Australian MVNOs have not. They only arbitrage.

In 2017, TPG, then an MVNO in Australia decided to become the country’s 4th network operator. However, plans were shelved to go it alone after the Australian government banned Huawei, which was TPG’s preferred vendor. In 2018, TPG and VHA decided to merge. The ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission) blocked the deal on competition grounds, insisting on having 4 network operators in the market. TPG appealed to the Australian Federal Court which gave the merger the green light.

In July 2020, the deal went through, illustrating that a national 3-operator structure makes sense because of the combined ability of the two companies to compete with larger rivals. We have similarly witnessed T-Mobile and Sprint merging to become the 3rd combined operator in the US. In Canada a combined Rogers & Shaw will create a robust wholly-owned national network and challenge the network – sharing advantage of Bell and Telus in wireless. In the process, investment by the combined entity will increase by $2.5 Billion across Western Canada, create 3,000 net new jobs and $1 Billion will be spent on a Rural and Indigenous Connectivity Fund.

Let’s turn to the fixed broadband side of connectivity in Australia.

Australia now has a nationalised wholesale broadband network, NBN (National Broadband Network). The NBN has been an outrageously expensive and highly controversial project from inception. It is still incomplete. The then Australian government conceptualised NBN in 2007 with an initial aim to cover 90% of the Australian population with fibre connectivity. It upped the coverage target to 93% in 2010. The project started in 2011 and by 2013 it had changed course after, the election of a new federal government. It went from being a fibre-only connectivity project to employing a variety of last-gen technologies due to concerns around cost overruns and expected delays in buildout. In 2014, it was estimated that upon completion the project would connect only 26% of households to fibre. In 2020, NBN announced that it was 99% complete, with service offered through fibre to the home, fibre to the node, cable, wireless internet and satellite.

Around the time shovels went into the ground, the project was estimated to cost AUD $43 Billion over its life. By 2018, the project budget was already at AUD $10 Billion over budget and in 2020, the government announced an additional investment of AUD $4.5 Billion further increasing the cost of this expensive, taxpayer-funded project.

This brings us to where we started.

On the wireless side, where Australia leads, competition has allowed the market to flourish. On the fixed broadband side, much forced tinkering has resulted in an expensive fragmented network, with slow speeds. Judged in its entirety, Australia’s broadband service looks mediocre.

Canada on the other hand is doing just fine with some of the fastest speeds being offered on both the fixed and wireless networks. Our government has a roadmap for our digital future and in partnership, we are moving ahead to bridge to digital divide with the quality and speed of communications networks that Canada is known for.

Charit Katoch, Director, Public Policy

¹ In the chart, the x axis labels reflect the ranking of each country on a global scale; Speedtest Global Index – Internet Speed around the world – Speedtest Global Index

² March 2021 estimates; Telegeography https://www2.telegeography.com/